Login Security Demystified

Last update February 10, 2026 (What’s new?)

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Password strength

- 3 Password guidelines

- 4 Supplements and alternatives to passwords

- 4.1 Password managers

- 4.2 Multi-factor authentication

- 4.3 Text message authentication

- 4.4 Email authentication

- 4.5 TOTP software authenticators

- 4.6 Hardware security keys

- 4.7 Biometrics

- 4.8 Passkeys

- 4.9 Federated identity and social login

- 4.10 Decentralized identity

- 5 How passwords are attacked

- 6 Guidelines for developers

Also see Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1 Introduction

Pop quiz: Which password is more secure?

A) Mbxsa38!

B) gacrpooofent

The answer is B. Surprised? People think A is more secure because it follows the typical rules for a “strong” password: at least one uppercase and lowercase letter, number, and special character. But the most crucial aspect by far of password security is length. A secure password is hard to guess. Password B is longer than password A, so it takes more tries to guess it, just like it takes more tries to guess a number between one and one hundred than a number between one and ten.

Even though password B is only four characters longer, it isn’t just a hundred times harder to guess, or even a million times harder to guess — it’s 78 million times harder! A cybercriminal using an extremely powerful password cracking system could crack password A in less than an hour, but it would take the same system thousands of years to crack password B.

We all have to use passwords. Over two thirds of the world uses the Internet. The average person has more than one hundred accounts. Unfortunately, the security risk from passwords is getting worse all the time. Around half of the vulnerabilities in cloud services are from weak or missing credentials. Compromised passwords have (perhaps) led to billions of dollars of personal and corporate loss. Reports and numbers vary, but tens of billions of passwords have been stolen and are available on the dark web. If your password is one of those, and you reused it at more than one site (which more than half of us do), your other accounts are at risk.

Most compromised passwords are extracted from data breaches, since too many companies do a bad job of protecting your data and because we humans don’t make strong passwords. But even the strongest password can be pilfered by malware or phishing, which account for billions of stolen passwords.

What to do? Passwords won’t go away any time soon. They’re being slowly surpassed by passkeys, but passkeys aren’t widely supported yet, and many existing passkey implementations are vexingly hard to use. In the meantime, the best way to protect yourself is to use strong passwords and take advantage of additional security measures such as multi-factor authentication.

Even when passkeys become predominant, passwords won’t disappear. They’re simple and universal. When newfangled login methods such as biometrics fail, or hardware security keys are lost, passwords are often still used as a fallback, so strong password security is as important as ever.

2 Password strength

Unfortunately, many people, even supposed experts, don’t understand what makes a password strong or weak. Most of the “how to make a strong password” guides are full of myths and misunderstandings. This section explains the true fundamentals of password strength. Section 3 provides simple guidelines on how to make strong passwords.

Why do we care about strong passwords? To keep the bad guys out. (Section 5 explains how the bad guys try to get in.) A secure password is almost impossible for a bad guy to crack.

A strong password is:

- Long – 12 characters or moreSee Aaron Toponce’s password length recommendations for more on why 12 characters is a sufficient minimum starting point.

- Unpredictable – random and hard to guess

- Uncompromised – not on a list of stolen passwords

- Unique – not reused for your other accounts

A weak password is:

- Short

- Predictable – uses typical patterns or words

- Common – the same as other people’s password

- Previously compromised

- Reused – by you in multiple places

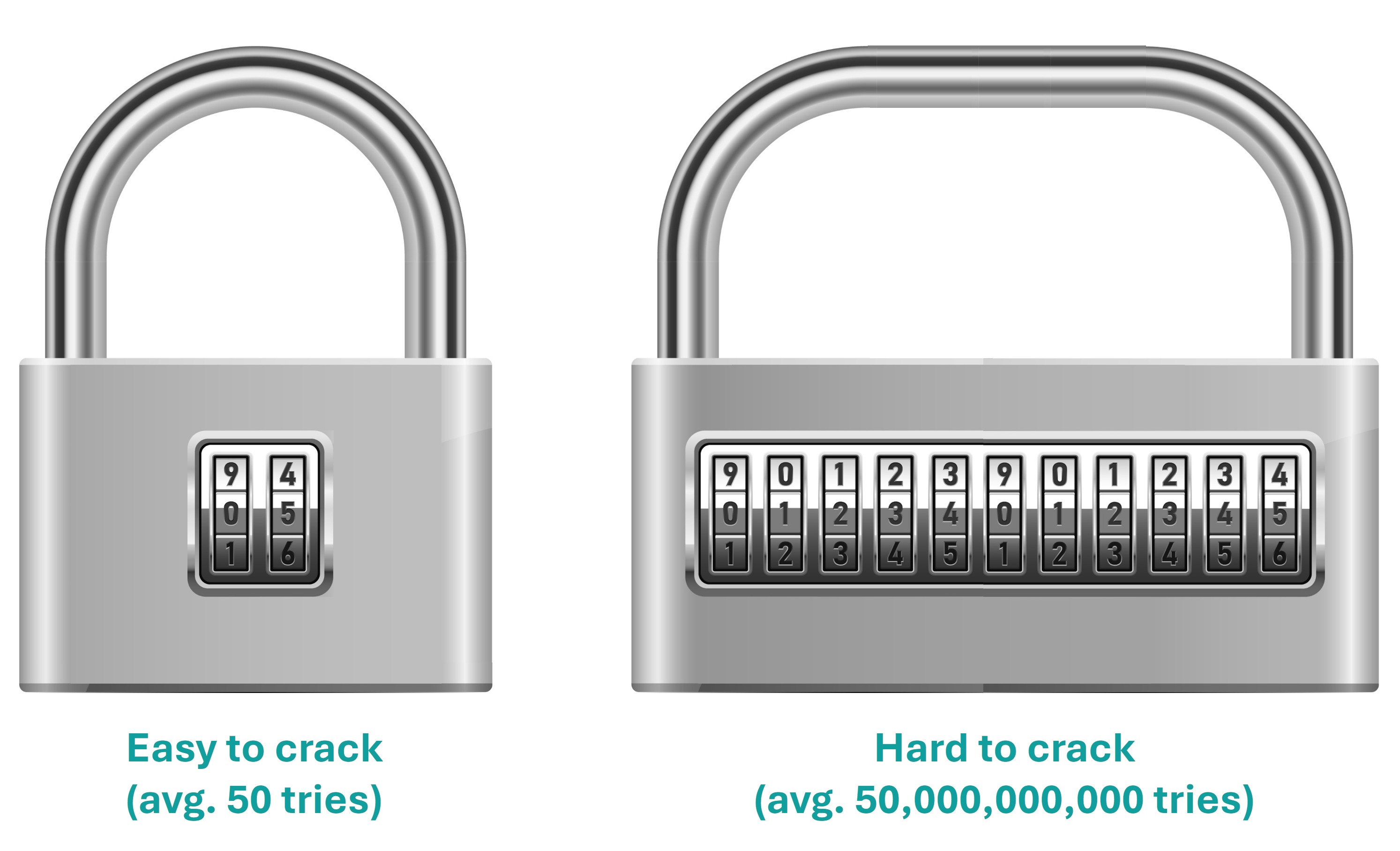

The one rule to rule them all is length. A longer password is a stronger password because it’s harder to crack.

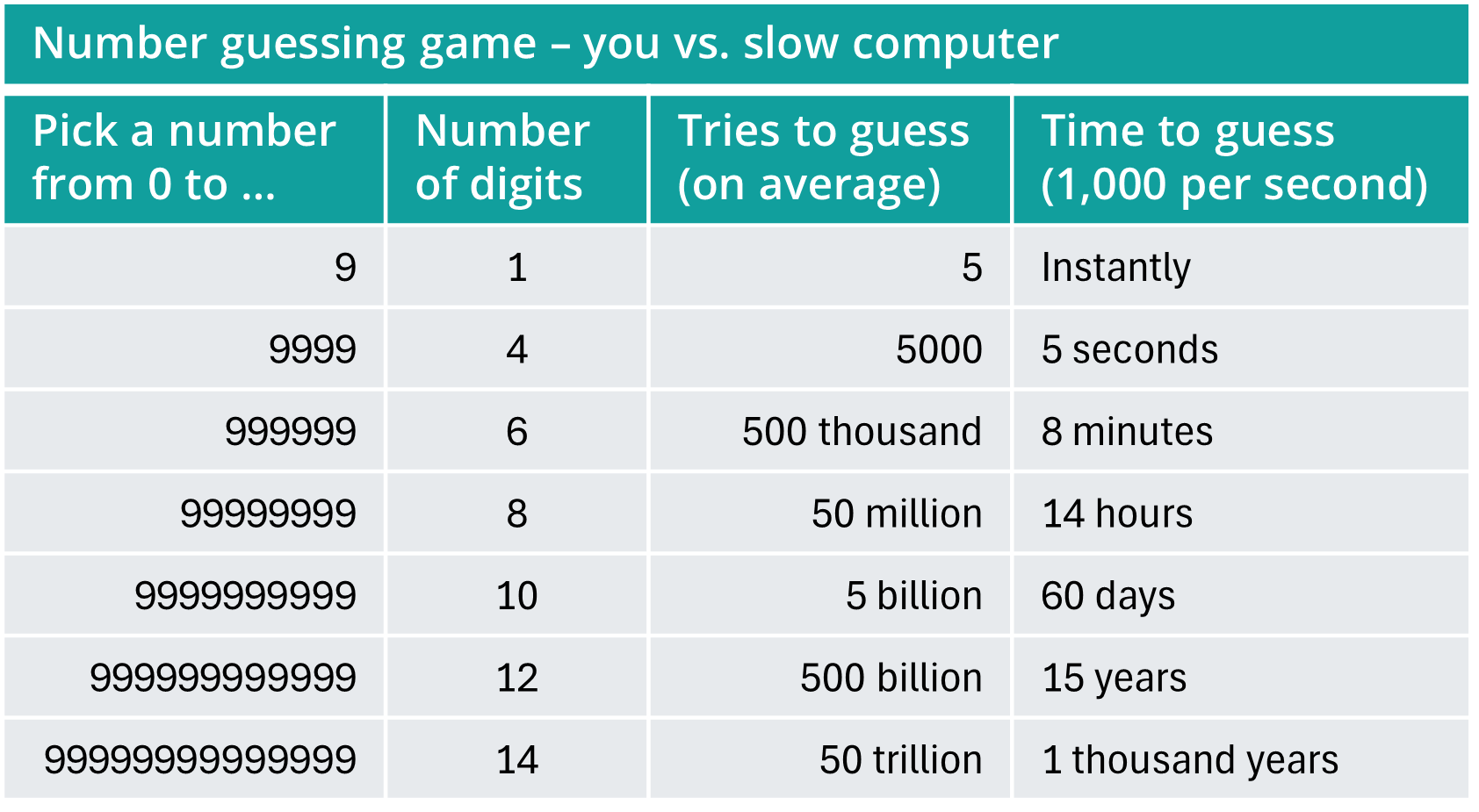

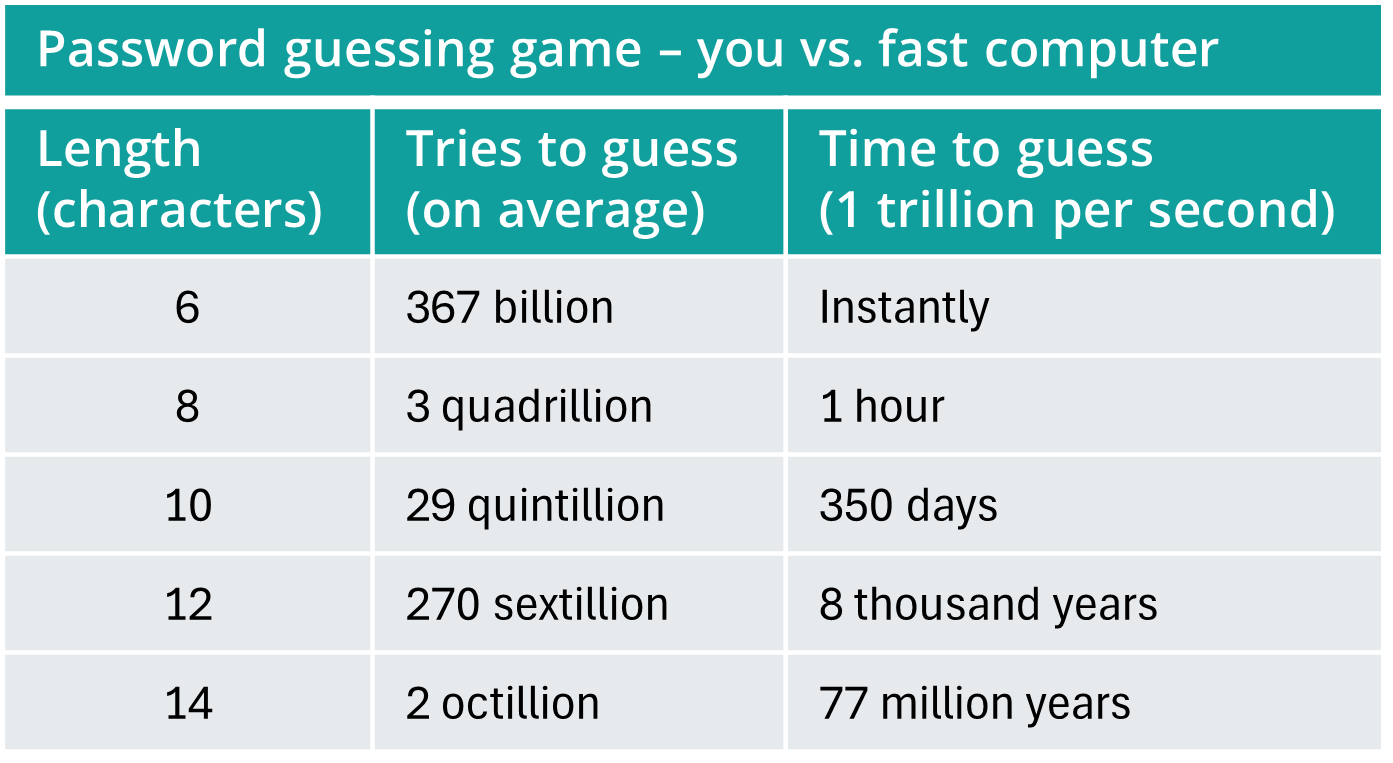

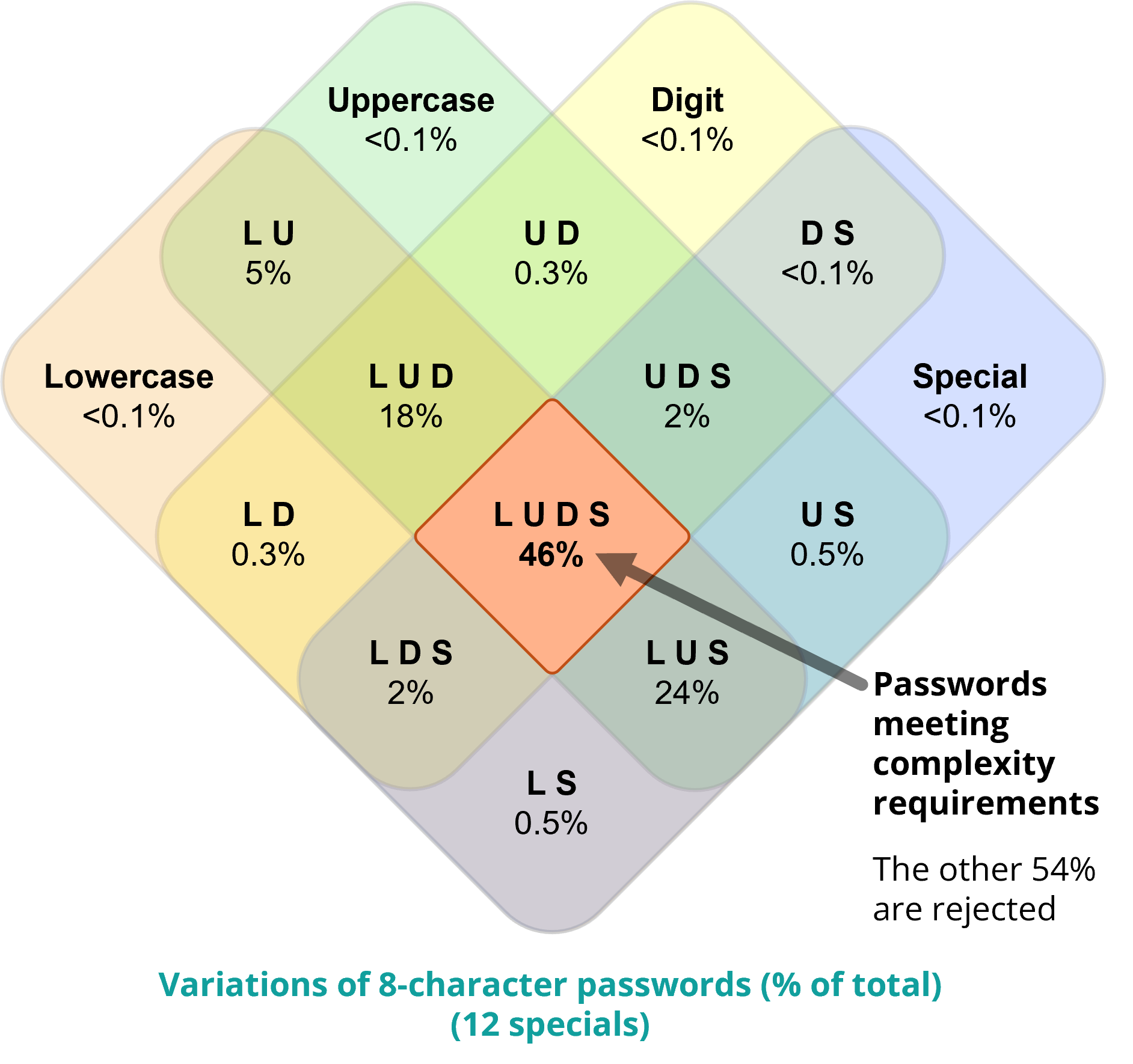

The math works like this: A single digit gives you ten possible values. If you add a second digit, you exponentially increase the possible values: 00, 01, 02, … 10, 11, 12, … 97, 98, 99 for a total of one hundred, which is ten times ten (102). If you add a third digit, you get one thousand (103) possible values. The same applies to password made of letters (52), numbers (10), and symbols (33), so a single character has 95 possibilities, two characters have 9,025 (952) combinations, three characters have 857,375 (953), and so on. An eight-character password has more than 6 quadrillion variations (6,634,204,312,890,625 or 958), and a twelve-character password has more than 540 sextillion (9512).

When guessing a random value, on average it will be found after guessing half the choices, so we can estimate that a random password of length L will take 95L÷2 guesses. (See the guessing game tables below.) However, attackers are smart and start by trying commonly used passwords, frequently used words, and prevalent patterns to significantly speed up the guessing game. Studies often show that knowing common patterns makes it possible to crack thousands or even millions of typical passwords in a few hours. (See section 5 for more on how passwords are attacked.)

Clearly, length is the key to a strong password. So why do so many services have rules that force you to create “complex” passwords, and why do so many password guides tell you that a “complex” password is a strong password?

Because a) they are sheep (“everyone else does it”), b) they don’t understand security, and c) they succumb to the prescient attacker fallacy, which is the faulty reasoning that an attacker knows how long your password is and what characters you used. Many discussions of password strength say things like “if your password is five numbers it will only take around 50,000 guesses, but if your five-character password contains mixed case, a digit, and a special character, it will take over 3 billion guesses.” This completely misses the fact that the attacker doesn’t know what characters you put in your password, so it will always take them over 3 billion tries (if they guess randomly, which they don’t).

This is part of the reason “complex” passwords are not more secure, and why services that force you to make your password more complex actually make things less secure. When the attacker knows there are restrictions, they can skip billions of guesses. For example, if the attacker knows that you must use at least one number, they won’t try passwords that contain only letters. The typical rule that requires at least one lowercase letter, uppercase letter, number, and special character in an eight-character password eliminates over three quadrillion passwords, or 54 percent! (See Password Constraints and Their Unintended Security Consequences.)

On top of this, complexity rules don’t meaningfully improve security, because humans are predictable. Analyzing patterns in cracked passwords shows that when people are required to follow the three-of-four rule (“you must use at least three of the following: uppercase, lowercase, numbers, special characters”), the most popular pattern is one uppercase letter followed by several lowercase letters, then two to four digits (“Spring2024” or “Qwerty123”). When faced with the four-of-four rule, people just add a special character to the end, usually “!” (“Qwerty123!”). See Password patterns for more on predictability.

Restrictions merely create a stronger blueprint for predictable passwords.

Remember, the goal is to thwart an attacker who knows about commonly used passwords and patterns and so-called “complexity.” The goal can be easily achieved with passwords that take too long to crack. The attacker will crack the easier ones first, then quit. The best way to increase crack time is to increase password length. In the password guessing game table above, you can see how each time you make a password one character longer it increases guessing time by days, then years, then centuries. This is for random guesses, but the principle holds true for smart guesses. In general, attackers give up after trying 8- to 10-character passwords and common longer passwords. A 12-character, unique password is very strong, and anything longer is even better.

3 Password guidelines

3.1 There are only three important guidelines:

1) Make it long. Make it as long as you reasonably can, at least 12 characters. If you don’t need to type it often, make it longer. If you need to remember it, try making a passphrase from three or more random words you’ll remember, such as “Clumsy-Chirping-Grandma.” (See the National Cyber Security Centre’s recommendations, and try a passphrase generator such as StrongPhrase or Bitwarden.)

2) Make it unique. Never use a password on one of the common password lists. Attackers use a technique called password spraying, where they try leaked usernames with common passwords, so if you use something like “password123!” your accounts are at risk! If you’re not generating random passwords, check uniqueness at websites such as Have I Been Pwned or Cybernews.

3) Don’t reuse it. Don’t use the same password for important accounts. Another technique used by attackers is credential stuffing, where they take your username and password stolen from one site and try it on hundreds of other sites. Of course it’s hard to keep track of more than 150 different passwords, which is the average. Some research suggests it’s beneficial to reuse passwords at low-value sites to reduce memory overload. You might want to use password variations for less important accounts: choose a long base password, then add something different to it that you’ll remember for each website.

A password manager will automatically do all three of these things for you.

3.2 Common additional tips (that are less important):

1) Don’t include personal or familiar information such as a date, name, email address, city, etc. This helps with brute force attacks (which use dictionaries of words, names, cities, dates, etc.), and it might prevent someone who knows you or can see your social media pages from guessing your password.

2) Don’t include words, unless it’s a passphrase. As pointed out by xkcd, the strength of a long passphrase is vastly better than a typical password, and it’s easier to remember. However, password cracking tools try dictionary words, so if your password is less than 14 or so characters, don’t put words in it.

3) Use a mix of symbols, uppercase and lowercase letters, and numbers. You might be forced to do this by draconian password rules at websites that don’t understand password security. Using a variety of characters makes your password a little stronger, but not as much as making it a little longer. (See Complexity, predictability, and strength, above, for an explanation).

3.3 Ignore common but mostly useless guidelines:

1) Don’t “use leet substitution” where you replace letters with similar-looking numbers or symbols. “Pa$$w0rd” or “@dm1n” is no more secure than “password” or “admin.” Password cracking tools have analyzed the leet patterns in compromised password lists and incorporated them into their algorithms. (See Leet Usage and Its Effect on Password Security for more).

2) Don’t “make your password complex” by reversing words (“drowssap”) using numbers or single letters for words (8 for “ate” or U for “you), random capitalization (“DroWssAp”), condensing phrases to initial letters (“Il2EgP” from “I like to eat green peas”), and so on. This faux complexity gives you a false sense of security.

3) There’s no need to “change your password regularly.” Research from CMU, UNC, CU, and others shows that periodic password changes usually do more harm than good, especially since people tend to make only small changes. Unless you know that a security breach has exposed your password, don’t bother changing it. It just eats up your time and adds to your password management load. Instead, visit Have I Been Pwned, Cybernews, or similar to see if any of your passwords have been compromised, and only then make a change. Or use a password manager that makes this check for you.

4) Don’t diddle with “Diceware to generate passphrases.” Some people swear by Diceware, but are you going to remember a set of strange words such as “dobbs bureau valeur ferric ababa synod”? And are you going to roll a die thirty times whenever you need a new password? The underlying concept of random, six-word passphrases is great, giving an average password length of 30 characters, but the process is cumbersome, and six words is overkill in most cases. Passphrases are good for critical accounts, as the master password for your password manager, and so on. Follow the National Cyber Security Centre’s advice and make a passphrase from three or more random words you’ll actually remember. If you can’t come up with a few random-ish words on your own, use a passphrase generator such as Bitwarden’s that uses the improved EFF lists (fewer rare words, easier to spell, no odd numbers and letter sequences).

3.4 Padding

An interesting suggestion from Steve Gibson is to strengthen passwords by padding them with runs of characters that are easy to remember and easy to type. His example takes the incredibly weak password “D0g” and adds 21 periods. As he explains, “D0g.....................” is stronger than “PrXyc.N(n4k77#L!eVdAfp9” because it’s one character longer, making it approximately 95 times harder to guess. This is a good way to meet guideline #1 above: make it long. You can come up with your own variations such as “((((((password))))))”, “////pass////word////” (preferably without actual words), and so on.

3.5 (Un)security questions

Every expert agrees that security questions are bad. Many accounts have been compromised through password recovery questions. Some answers are very popular (around 30 percent of people worldwide say blue is their favorite color and around 20 percent of Americans say pizza is their favorite food), questions and answers tend to be repeated across accounts, and unencrypted answers are often revealed in data breaches.

Someone targeting your account may be able to dig up enough information about you to answer recovery questions — your hometown, the street you grew up on, schools you attended, where you got married, etc. Pew Research shows that 37 percent of Americans have never moved from their hometown.

If security questions are optional, leave them blank. If you are forced to answer them, obfuscate your answers and make them different for each website. For example, even if your “favorite food” is pizza, you could answer “pizzPayP” for PayPal and “pizzBoA” for Bank of America. (Not that these specific services are foolish enough to use secret questions, but you get the point.) Some services require multiple questions and don’t let you use the same answer, so you could answer “MyMotherIsACar_drycln_school,” “MyMotherIsACar_drycln_pet,” “MyMotherIsACar_drycln_job” for questions that your dry cleaner’s website asks about your high school, pet, and first job. (See NordVPN’s Which security questions are good and bad? for more suggestions, keeping mind that all security questions are bad.)

3.6 Writing down passwords

It’s fine (really!) to write your passwords down, as long as you keep the list secure, such as in a locked drawer, secret location, or encrypted file. If recording your passwords makes it easier for you to use long, strong ones, then by all means do it. Or use a password manager. Just don’t write them on sticky notes scattered around your desk.

Don’t rely on your memory. The Internet is full of sad stories from people who forgot the password they were sure they could remember.

If you keep the list on a computer or phone, make sure it’s protected by a unique and extra-long password. There are many ways to protect a file. Apple Notes and Windows OneNote let you password-protect a note. You can keep a file safely in Apple iCloud, but make sure your AppleID password is very strong. A password-protected Zip file or a file encrypted with VeraCrypt or similar tools can be stored almost anywhere, including in the cloud. You can use an encrypted USB drive. Microsoft OneDrive includes a "personal vault" to securely store files. The Apple Disk Utility lets you create a password-protected disk image. In Windows Pro you can encrypt a folder.

On the “we’d rather not think about this but it’s practical” side, someday you will die, and your loved ones may desperately need to access your important bank accounts, brokerage accounts, cryptocurrency keys, etc. so it’s a good idea to give your list of passwords to a trusted person or two.

3.6.1 Emergency kit

An important step, especially if you use a password manager or passkeys, is to make an emergency kit or security sheet and put more than one copy in safe places. It’s basically a list of your most critical passwords, including your computer login password, 2FA recovery codes, passkey recovery codes, and other backup codes.

Since many accounts use email for 2FA, include everything you need to access your email accounts, including passwords and any recovery codes. This avoids the dilemma where your password manager requires you to enter a 2FA code but you can’t log into your email to get the 2FA code because your email password is locked in your password manager.

You can use a sheet of paper or a computer file. If a file, be sure to password protect it. See the suggestions above in 3.6.

See Bitwarden security readiness kit and Password Manager Emergency Sheet for examples. See djasonpenney’s emergency kit page for more advice (specific to the Bitwarden password manager, but the principles apply in general).

3.7 App passwords

Some services, including Apple, Google, and Microsoft, allow you to create app passwords (also known as application-specific passwords) that can be used in place of your regular password. These are less secure than passwords with 2FA or passkeys, and are not recommended for general use, but may be needed for older or less secure apps and devices, such as those that access your email, contacts, and calendar (e.g, Outlook 2010 or older, BlackBerry phones, Android 4 or older, iPhone iOS 10 or older, Xbox 360, some smart TVs, and security cameras that send email alerts.)

App passwords are typically long and randomly generated. You can’t choose them yourself. You need to enable 2FA before you can ask the service to generate an app password. (This doesn’t mean the app password requires 2FA, since it specifically bypasses 2FA, but it’s a required step to secure your main password). After you copy and paste it into the app, you usually can’t go back and get another copy; you have to generate a new one.

App passwords are not tied to specific apps or devices, but you should generate a new app password for each one. If an app password is compromised, you can revoke it without changing your main password. If you change your main password, all your app passwords are usually automatically revoked. App passwords may expire after a year or so. Most app passwords can’t be scoped, that is they can’t be restricted to specific actions or information in your account, so they still need to be used as carefully as a regular password.

4 Supplements and alternatives to passwords

Security experts all agree that passwords are not secure. If everyone created very strong passwords and remembered them, it wouldn’t be so bad, but we know most people are bad at coming up with good passwords. Passwords are a shared secret between you and a service, so they can be shared, guessed, stolen, and cracked. The more secure a password is, the harder it is to remember it. Services store a scrambled version of your password, and although there are robust techniques to protect password data, too many services don’t guard them properly. Computers get faster every year, making it easier to crack passwords. Quantum computing is just around the corner, and it will make password cracking even faster. Last but not least, passwords are a pain to type in, although password managers help with this.

There are various approaches and industry initiatives to move beyond passwords with more secure alternatives, but they all have drawbacks when compared to the simplicity of storing passwords in your brain. Most alternatives rely on a physical device (such as a computer to respond to an email or a mobile phone to check your fingerprint), so if the device is not available or not working, you’re either locked out or you have to use a workaround.

Some approaches add a second layer of security on top of a password. Because there are two or more factors, the password and an additional step or two, this is called multi-factor authentication (MFA).

Another approach is passwordless authentication. Some methods are kludgy, like e-mail based “magic links,” and other methods such as such as passkeys are simple, secure, and starting to be embraced. Some passwordless authentication for websites has you respond to a prompt on your phone or tablet. Apple and Google have built this into their phones. Other companies such as credit card services use their own app. The biggest problem with this approach is that each implementation is proprietary, nothing is consistent, and you may not have the right device or have the right app installed. Passkeys are on track to eventually replace and simplify the passwordless patchwork.

Passwords will likely never go away, but over time we’ll see new authentication techniques be more widely used.

The rest of this section covers the most common additions and replacements to passwords.

4.1 Password managers

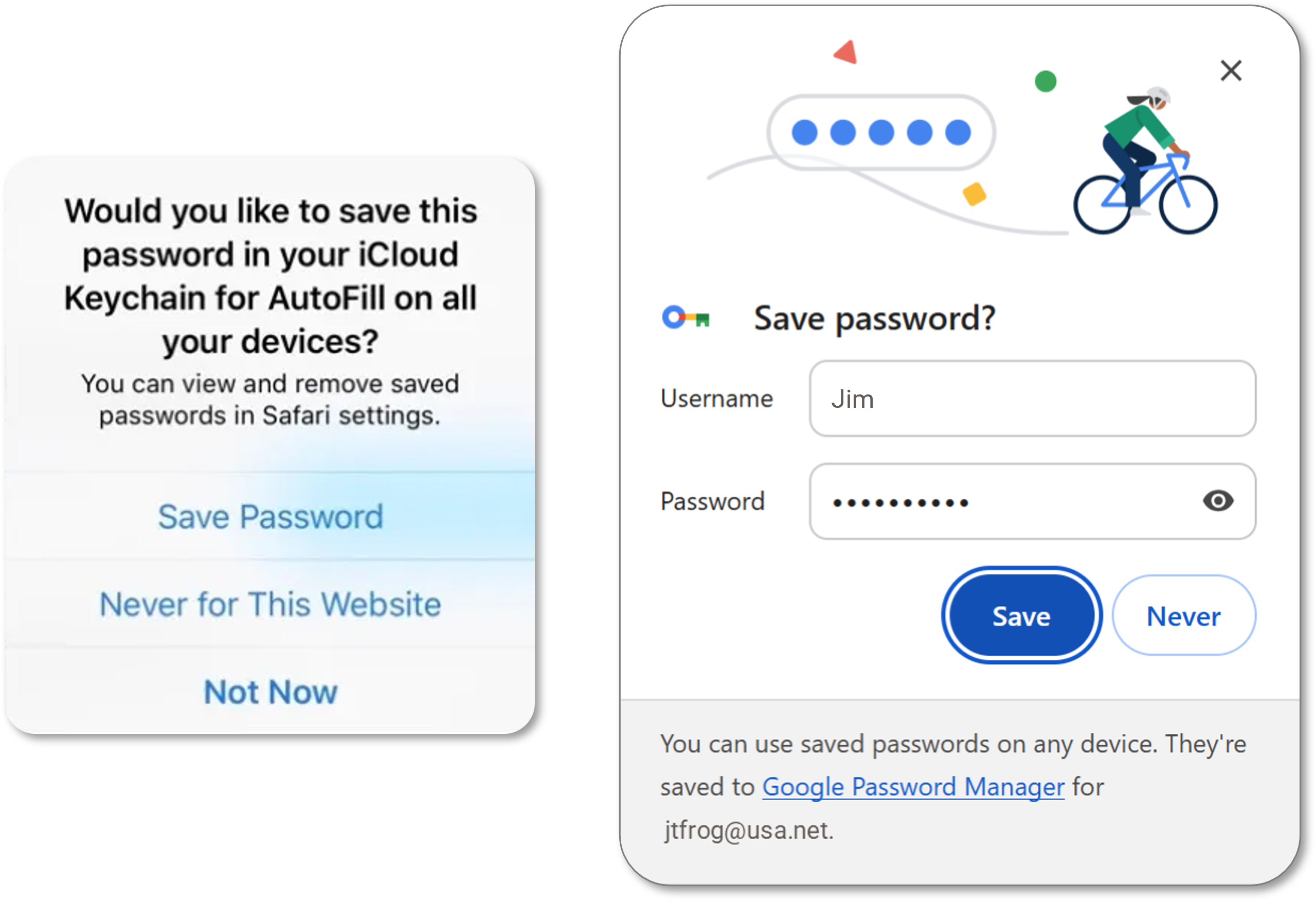

A password manager is software that generates passwords for you and automatically enters them as needed, so you don’t have to remember them or type them. Most modern browsers have a built-in password manager to remember your existing passwords and to suggest new ones for you. Many people don’t realize that when they visit a website and their username and password are filled out for them, it’s the browser doing it, not the website.

Alternatively, standalone password manager applications can be installed on multiple platforms, with extensions that work on multiple browsers.

Around 36 percent of US adults use a password manager, compared to 15 percent worldwide. Of those who use a password manager, around 60 percent use Apple or Google’s built-in browser password manager, and the remaining 40 percent use a standalone password manager application, with a small fraction using other browser’s password managers.

There are tradeoffs between built-in password managers and standalone password managers. Saving passwords and passkeys in your browser is free and convenient, and autofill works better, but you’re locked into that model of browser. Standalone password managers have extra features such as saving credit card numbers and other info, organizing entries, sharing passwords and passkeys with others who use the same password manager, integrated TOTP authenticator, and more, in addition to working across multiple platforms and browsers. The security differences are not huge, so pick the option that’s more convenient for you. See Password manager security for more.

A dedicated password manager uses strong encryption to securely store all your passwords and passkeys. One master password gives you access to all your other passwords and sensitive data. A good password manager requires you to protect the master password with a passkey or 2FA to prevent an attacker from getting hold of all your passwords. But, because all your passwords and other information are locked behind a single master password or passkey, the following is very important:

- Don’t store your master access information inside the password manager. Otherwise you’ll end up in a catch-22 situation where the key to open your vault is locked inside your vault. This applies to your master passkey, or if you use a password and email 2FA, it applies to everything you need to access your email account (passkey/password/2FA).

- Don’t assume you’ll remember your master password. People worry about their passwords being stolen from the password manager, but what happens much more frequently is they forget their master password and have to reset all their accounts. A good solution is to create am emergency kit to store everything you need to access your password manager and your email account(s).

Advantages of password managers:

(Most of these apply to both standalone and built-in password managers.)

- Strong passwords – Password managers create strong (long, unique, and unpredictable) passwords.

- No memorization – You only need one, strong password for the password manager, which protects all your other passwords. (Built-in password managers usually use your device’s password.) You no longer have to reset passwords that you forgot.

- Autofill – Your username and password is automatically typed for you.

- Reduce errors – No wrong password problem.

- Phishing protection – Passwords are associated with only one domain, so if you are tricked onto a fake website, the password manager won’t enter your password for an attacker to steal.

- Support for passkeys – Most password managers can manage your passkeys.

- Breach notification – Some password managers have a service to notify you if your username or password is leaked in a data breach.

- Secure storage – Standalone password managers securely store passwords and passkeys with strong encryption based on a master password, often with a second factor. Built-in password managers typically store the the passwords in OS-protected storage, which is very secure unless someone has your device and can unlock it.

- One-time passwords – Some standalone password managers can generate one-time passwords (OTPs) and autofill them.

- Sharing – Some password managers allow you to securely share your password with someone using the same password manager. (Of course, this is only a good idea if the password is for a shared account.)

- Info vault – Some password managers can securely store additional information such as credit cards, account numbers, answers to password recovery questions (which can be deliberately wrong to increase your security), personal information, and even files.

- Corporate deployment – A few standalone password managers allow an organization to centrally manage employee passwords.

Disadvantages of password managers:

(Most of these apply to both standalone and built-in password managers.)

- Single point of failure – Standalone password managers don’t store your master password. This is for your security, but it means the company can’t help you recover your passwords and other information. If you forget your master password and lose your recovery info because you didn’t create an emergency kit, there is no way to get your passwords back. (See

- Incompatibility – Password managers don’t work with many apps and devices (such as smart TVs), and might not work on some websites, in which case you must manually enter a long and complicated password after looking it up in your password manager.

- Unavailable on non-owned devices – If you want to use someone else’s computer or phone, or a public computer, your password manager is not there to log you in. If the password manager is available on another device you have with you, such as your phone, you can look up the password and type it in, but this is cumbersome and could expose you to a phishing attack.

- Cost – Some are free, including those built into browsers, but the better ones require purchase or subscription.

- Complicated – Some standalone password managers may be a little tricky to learn and use.

- Attackable – Password managers can be compromised, especially if your device is infected with malware. Malware, including malicious browser extensions, can see your passwords when they’re autofilled by the browser or a standalone password manager. If your passwords are synced, an attacker can get them all if they break into your account or have your master password and 2FA. Breaches of encrypted password manager data in the cloud are unlikely but have happened (also see Password Managers Hacked: A Comprehensive Overview).

- Loss of control – Your data is managed by a company, not you. It’s usually stored in the cloud, where you have no control over security. (There are a couple of password managers that give you “self-hosting” control over your data.)

- Legacy insecure passwords – Research shows that almost half the users of password managers don’t use the secure password generation feature, and instead load in their old, insecure passwords. This isn’t the fault of the password manager, but it creates a false sense of security.

- Unavailability – If the password manager service can’t be reached, or the software fails, you might not be able to access your passwords.

- Phishable – Password managers prevent phishing for site-specific passwords by refusing to enter them into the wrong website, but the autofill feature of some password managers has been fooled by hidden forms or iframes, and you could be fooled by a fake app or website that looks like your password manager, where you enter your master password and give the attacker access to all your passwords. (Which is why you should always use MFA or a passkey.) (See 5.3 for more on phishing.)

- Password mismatch – Some websites may appear to accept a password but internally strip characters or truncate to a maximum length, so the generated password doesn’t work, and your next login attempt fails.

4.2 Multi-factor authentication

A factor is way of confirming your identity. The most common factor is a password. The three primary types are:

- Something you know (knowledge) – unique information such as a password, pin, or unlock pattern.

- Something you have (possession) – a phone app, a text message, an email message, a USB key, or such.

- Something you are (inherence) – a physical characteristic or biometric such as your fingerprint, face, retina, or voice.

Additional factors are sometimes employed:

- Somewhere you are (location) – at your home, in your car, at the office, or so on.

- Something you do (behavior) – the rhythm of your typing (keystroke dynamics), the way you tend to move a mouse or interact with a touchscreen, or so on. Note that unlike biometrics, a behavioral factor is dynamic and can change over time.

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) means you are asked for two or more factors to provide extra security, like being required to provide both a photo ID and a birth certificate when applying for a passport. The first factor is usually a password or other secret, but any combination of factors could be used. When there are two factors it’s often called two-factor authentication (2FA) or two-step verification (2SV).

The obvious advantage of using MFA is improved security. MFA reduces the risk of account compromise by over 99 percent, even if your password is cracked and leaked. The obvious disadvantage is inconvenience. Studies indicate that around 60 percent of companies globally use MFA. The primary reason cited for not using MFA is inconvenience.

The strongest authentication factor is biometrics, measuring unique personal characteristics or behaviors that can’t be shared or mimicked. Biometrics are often the simplest, quickest, and least disruptive. You just look at a camera or touch a screen. Biometrics are rarely used as a single factor, and government or industry regulations often require that they only be used with another factor such as device possession or a password or secret key.

The second strongest factor is device possession, which obviously requires you to have a device, typically a phone. Once you’ve logged in on a device, it’s trusted for future authentication. For later logins on that device, you may be able to skip additional authentication steps. When logging in from somewhere else, especially a new device, you may be asked to authenticate by confirming on your trusted device. For example, a bank website might have you confirm your login by responding to a notification on the bank’s app on your phone, or a website might give you a QR code to scan with your trusted phone.

Additional common authentication factors are:

- Text message – see 4.3

- Email – see 4.4

- Phone call

- Software authenticator – see 4.5

- Hardware security key – see 4.6

Part of the reason passkeys are so secure is they require device possession and often include biometrics. (See Are passkeys MFA? for more.)

An important issue with MFA is phishing resistance. Some factors are inherently phishing resistant: biometrics, device possession, and FIDO hardware security keys. Other factors are not: passwords, text codes, emailed codes, and codes from hardware or software authenticators. The key difference is whether or not there is a shared secret that both you and the service have, that can be easily given to an attacker. Emailed links containing long codes are in the grey area between, as they can’t be easily told to someone, but they can be copied and pasted, or an attacker can log in with your stolen credentials and then trick into activating the link to confirm the login.

2FA Directory helps you check what kinds of 2FA a website supports.

4.2.1 Authentication comparison

The strength of an authentication factor depends on how well it protects the secret that authenticates you, including how well it resists phishing, replay, and other attacks.

Phishing resistance is the most important element, since phishing is the most common attack. Shared secrets are the weakest point, since they can be phished, intercepted, or stolen from either party. Private keys are not shared, so they can’t be intercepted or stolen from a service. (See public/private keys.)

Although a passkey is not an authentication factor, it combines multiple strong factors into one login step when the website or app requires user verification, so it’s included in the table to show relative strength. (See Are passkeys MFA?)

| Method | Security | Secret | Strength | Weakness | Level† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passkey (bound to hardware security key) |

Highest | Private (key) |

|

|

AAL3 FIDO 2–3 FIPS 2–3 EAL 4–6 |

| Passkey (bound to computer or phone) |

Very high | Private (key) |

|

|

AAL32 FIDO 2–3 FIPS 2 EAL 4–5 |

| FIDO2 non-discoverable | High | Private (key) |

|

|

AAL2 FIDO 2–3 FIPS 2–3 EAL 4–5 |

| U2F hardware security key | High | Private (key) |

|

|

AAL2 FIDO 1–2 FIPS 2–3 EAL 4–5 |

| Passkey (synced) |

High | Private (key) |

|

AAL2 | |

| Biometrics (fingerprint or face) |

Medium high | None (unlocks key or app) |

|

|

None (not typically a standalone factor) |

| TOTP authenticator (hardware or software) |

Medium | Shared (seed) |

|

|

AAL2 (HW: FIPS 1–2 EAL 4–5) |

| Push notification (on trusted device) |

Medium | No secret |

|

|

AAL1 |

| Emailed link (“magic link”) |

Low | Shared (URL) |

|

|

AAL1 |

| Text OTP (SMS) or voice OTP | Very low | Shared (code) |

|

|

AAL1 |

| Emailed OTP | Very low | Shared (code) |

|

|

AAL1 |

| Password (alone) |

Lowest | Shared |

|

|

AAL1 |

|

Note: Other factors such as look-up secrets (e.g., a grid of printed codes) and a QR code scanned by a trusted device are not included. 1 A passkey on a mobile phone can be used on other devices by scanning a QR code. However, Apple and Android passkeys are almost always synced, not device-bound. 2 Passkeys only qualify for AAL3 when non-exportable (not synced) and bound to platforms with FIPS-validated secure hardware and proper configuration, such as Windows Hello, otherwise they are AAL2. 3 Whether or not passkeys are protected by special security hardware depends on the credential manager. Android, Windows, and Apple protect passkeys with hardware security modules (HSMs). Other password managers don’t. Cloud storage of passkeys is often protected by HSMs. 4 Synced passkeys (and passwords) are protected by the security of the sync fabric. In other words, the ways you can access your Apple, Google, Microsoft, or other password manager account determines the security of the credentials stored in that account. This also applies to password managers that are self-hosted or use local storage, even if the credentials are not synced. 5 Once you choose an ecosystem in which to store passkeys and passwords, they may be tied to that ecosystem. For example, if you choose Google Password Manager, your credentials can be used from Android devices and any other device running the Google Chrome browser. Ditto for Apple devices or a device running the iCloud app. The same applies to standalone password managers. Switching to a new ecosystem can be difficult. You can often export and import passwords, but passkeys are harder to move. This is changing as the FIDO Credential Exchange Protocol (CXP) is adopted more widely. 6 Context (login location, service name) helps to reduce accidental approval and to spot phishing attempts. Matching a number, picture, or text shown on the login page to a choice on the device mitigates blind approval and push bombing (where the attacker triggers hundreds of notifications in hopes that you will approve one). Without these protections, push notification is less secure than the cryptographic binding in TOTP authentication. 7 The risk of SIM swap is low and can be further mitigated by enabling SIM protection at carrier. 8 Email accounts are the primary target of attackers. A weak password and no 2FA leaves the account and email-based 2FA vulnerable. Email accounts should be protected by a strong password and 2FA, or a passkey, but they rarely are. For this and other reasons, NIST rejects e-mail as an authentication factor. |

|||||

|

† Various agencies and standards bodies define levels of security. FIDO, FIPS 140, and CC EAL require that independent labs certify products or components, not technology or methods, so this table shows typical ranges for products implementing an authentication method.

|

|||||

4.3 Text message authentication

Instead of entering a password, or as a second factor in addition to a password, you receive a text message at your verified mobile phone number with a one-time code that you type (or copy/paste) into the login screen. This is the most widely implemented second factor. It’s often called SMS authentication but can use any mobile messaging protocol such as SMS (Short Message Service), MMS (Multimedia Messaging Service), RCS (Rich Communication Services), or Apple iMessage.

Advantages of text-based authentication:

- Fast delivery – text messages are usually delivered within seconds.

- Widely available – over 90 percent of Internet users have a phone.

- Relatively easy to use – you must check your phone and type or copy a code, but you don’t have to set up another authentication device.

- Relatively simple for a service to implement.

- Marketing potential – for a service, this creates an opportunity to get phone numbers.

Disadvantages of text-based authentication:

- Vulnerable to phishing – a fraudulent party may try to get you to reveal the code.

- Not fully secure – SMS and MMS text messages are not encrypted; however, the risk from SIM swapping or interception is highly overrated, see “Is SMS insecure” below.

- Reliance on a mobile device and network – if you don’t have access to your phone, or you’re in a place where there is no mobile service, you may not be able to log in or may have to resort to a more roundabout method.

- You may be uncomfortable giving out your phone number, which may be shared or abused by the service

- Some sensitive environments don’t allow mobile devices.

4.4 Email authentication

In addition to a password, or sometimes in place of a password, a message is sent to your verified email address. The email contains either a code (a sequence of letters and/or numbers) or a link (a web URL, sometimes called a “magic link”) with a code embedded in it. These are usually one-time codes, which means they expire after a short period of time, and once you use them, they don’t work again. (This is for security, so that if someone gets into your email they can’t log in to your accounts using codes from old email messages.) When there’s a human-readable code, you type (or copy and paste) it into the login screen. When there’s a link, you click or tap on the link to log in.

Advantages of email-based authentication:

- Widely available – Over 90 percent of the world uses email.

- Resistant to phishing if a link is used instead of a short code – A fraudster on the phone usually won’t ask you to read out a long link, unless the code inside the link is short and easy to spot. But they could ask you to text it, email it, message it, or paste it into fake website.

- Relatively easy to use – You must open an email app, but you don’t need to have a phone or another authentication device.

- Single-use – Codes or links usually expire and can’t be re-used, which adds a bit of security.

- Reduces memory load – You don’t have to remember a password.

- Customers may be more comfortable providing their email address than their phone number (e.g., for text-based authentication)

- Inexpensive or free – Avoids the possible charge of receiving a text message.

- Simple for a service to implement – Cheaper than sending text messages

- Marketing potential (for the service, it creates an opportunity to get customers’ e-mail addresses)

Disadvantages of email-based authentication:

- Lowest security – Weaker than text-based authentication. If an attacker compromises your email account, they can attempt to take over your accounts using email authentication. Even though links usually expire, an attacker may be able to use them to trigger a retry.

- Vulnerable to phishing – a fraudulent party can try to get you to share the code or paste the link into a fake website.

- Inconvenient – You have to check email. There may be a delay in receiving the email or it may get lost. You may have to switch between desktop and phone if you’re logging in on one device but get your email on a different device.

- Can be mistaken for spam – You must take extra time checking your junk mail folder. Strong spam filters may block you from accessing the authentication email at all.

- Relies on email – If you can’t access your email, you may not be able to log in or may have to resort to a more roundabout method.

- Marketing – You are required to provide your email address, which may be abused by the service.

4.5 TOTP software authenticators

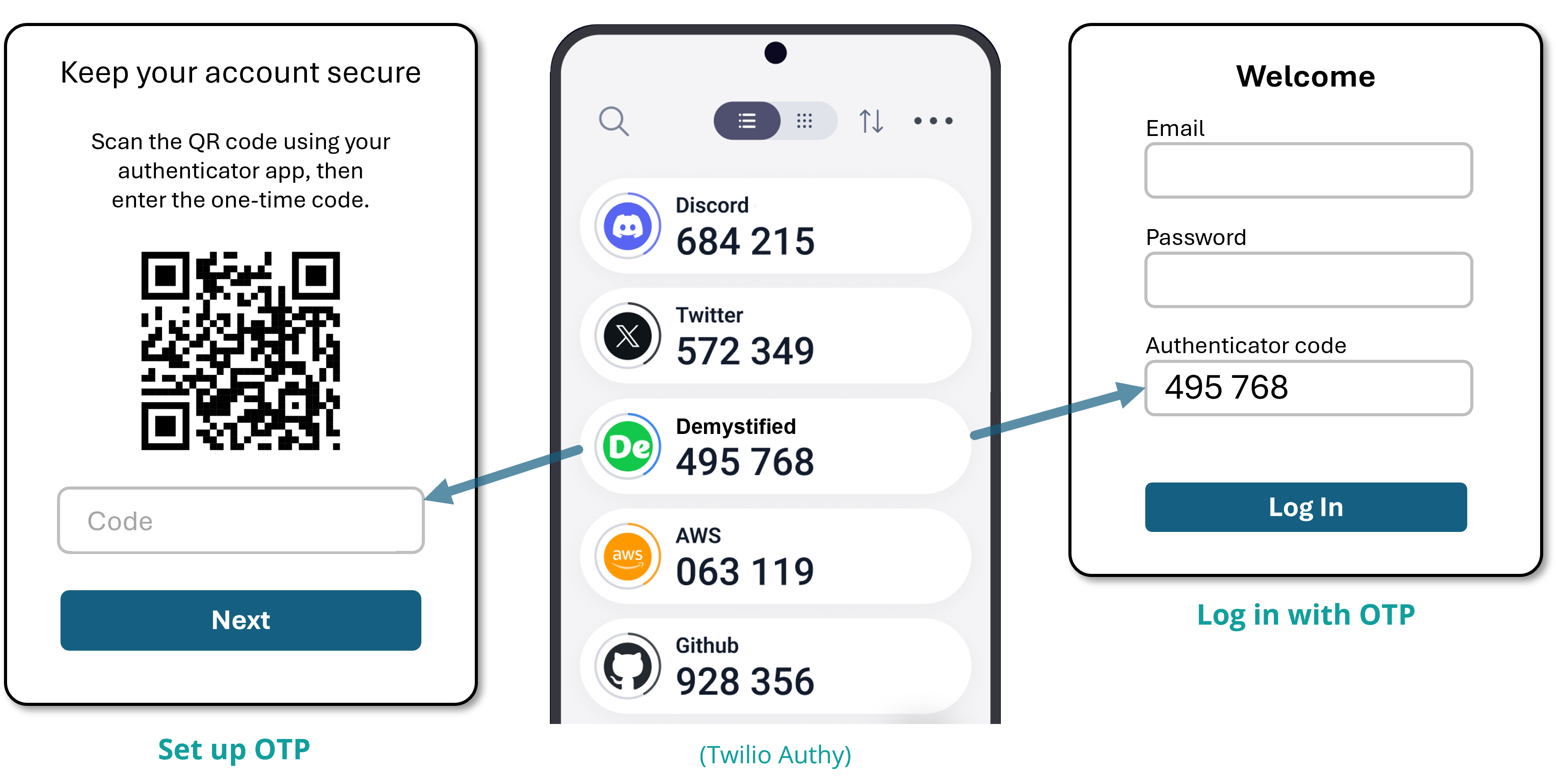

A software authenticator (also called a 2FA app, OTP app, soft token, or software-based code generator) displays short codes that you type in as second login step. The code, usually six digits, is a time-based, one-time password (TOTP), which changes every 30 seconds or so. Many software authenticators run only on mobile phones or tablets, but the code can be typed in on a computer.

There’s a one-time setup process, where the authenticator app talks to the service that you want to log into and receives a shared secret key, or seed, often via scanning a QR code. After that, the app displays the current authentication code for each registered service, based on the current time. When you log in to a service, you check the authenticator app and type the current authentication code. The service generates its own code based on the secret key and the current time. If the two codes match, then you are authenticated.

Popular software authenticators include 2FAS, Aegis Authenticator (Android only), Apple Passwords (Keychain), Authy, Ente Auth, Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, and Duo Mobile. Most password managers have a built-in TOTP authenticator.

Most software authenticators provide encrypted backups or exports that make it easy to move to a new phone or another device. However, some backups/exports can’t be moved between different types of devices, such as Android and iPhone.

Some software authenticators also support HOTP (hash-based message authentication code [HMAC]-based one-time password, often called event-based OTP), where the code changes each time there’s a new login instead of every 30 seconds or so. HOTP is not as common as TOTP.

Software authenticators are being superseded by passkeys, which don’t require looking up numbers and typing or copying/pasting them.

Advantages of software authenticators:

- Secure – One-time passwords can be used only once, and time-based passwords change frequently, reducing the window of attack. There is no communication between the authenticator and the service during code generation, so nothing can be intercepted.

- No Internet connection is needed – After the initial setup, the codes can be generated and used offline.

- Simple – Setup is usually easy, often only requiring you to use the authenticator app to scan a QR code presented by the service. Entering a six-digit code is not too difficult.

- Most are free.

- Relatively inexpensive for implementers to support.

Disadvantages of software authenticators:

- Vulnerable to phishing – Attackers can try to fool you into telling them the code or entering it into a malicious website.

- Vulnerable to attack – The key is a shared secret stored in the authenticator and at the service. If the key is stolen from the service, or if your computer or phone is compromised or stolen, legitimate codes could be generated.

- Third-party trust – TOTPs add another step between you and the service you’re logging into, requiring you to trust the authenticator to be secure.

- Inconvenient – Requires you to open and use an application, usually on a mobile phone, and type or paste a code.

- Additional point of failure – If the app doesn’t work or the phone is not available, you may not be able to log in, or you’ll have to use an alternative login. If you get a new phone and don’t have a backup of your MFA accounts, you’ll have to redo everything.

- Could be prohibited – Some sensitive environments don’t allow mobile devices.

4.6 Hardware security keys

Note to readers: Unless your company requires you to use a hardware key, or you’re a security fanatic, you should skip this section. It gets rather complicated.

A hardware security key (alternatively called a hardware authenticator, hardware token, FIDO key, OATH key, OTP token, or hardware-based code generator) is a thumb-sized or credit card-sized device that stores cryptographic keys as part of a second login factor or in place of a password. In some cases, it’s a secure chip built into your phone or computer instead of an external device.

There are three main protocols used by hardware authenticators:

- OATH (TOTP and/or HOTP) – The hardware equivalent of a (software authenticator, where the device generates a one-time password

(OTP), usually six digits. This is the least secure of the three. See 4.6.1 for details.

(Note: this is more precisely an OTP authenticator, which is different from a FIDO authenticator, which uses public/private keys.)

(Note: OATH is not the same as OAuth.) - FIDO U2F/CTAP1 – A standard interface for connecting to compatible browsers and operating systems over USB, NFC, or Bluetooth to provide a second login factor using public/private keys. See 4.6.2 for details.

- FIDO2 – A standard for passwordless authentication using passkeys that can be stored in a hardware security key. FIDO2 is the most secure of these three protocols. See 4.8 for more on passkeys.

Many hardware keys support all three protocols. Some hardware security keys support additional protocols such as PIV/FIPS 201 for smart cards, OpenPGP, and Yubico OTP, but these are less common and not covered here.

There are four common ways for hardware keys to connect when logging in:

- USB – You plug the hardware key into a USB port on your computer or phone.

- NFC – The hardware key uses wireless NFC (near-field communications; the same technology used for tap-to-pay) to send a login code to your phone, tablet, or (rarely) computer.

- Bluetooth – The hardware key uses wireless Bluetooth to send a login code to your phone, tablet, or computer. In some cases, your phone can act as a hardware security key using Bluetooth.

- Display – The hardware key displays the one-time code on its built-in screen for you to type into the login page. This only applies to TOTP and HOTP.

Hardware security keys are becoming less common now that modern phones and computers can use passkeys for secure, passwordless login, except in cases where high security is needed, in which case FIDO2 hardware security keys can hold the passkeys more securely.

Hardware security keys are often centrally deployed by large companies.

Popular keys from reliable companies include the Yubico Security Key or YubiKey, Google Titan, Token2, Deepnet SafeKey or SafeID, HID Crescendo, Kensington VeriMark, Nitrokey, SoloKey, Feitian OTP, RSA SecurID, Symantex Vip, Thales eToken Pass, Thetis Pro, and Vasco Digipass Go.

4.6.1 OATH OTP hardware security key

An OATH hardware key (also called an OATH token, OTP token, or OTP generator) is the hardware equivalent of a software authenticator that generates one-time codes (OTPs), usually six digits, that you enter during the login process. The primary advantage of a hardware authenticator is that it’s more secure than a software authenticator, and a single hardware key can easily be used across multiple devices (laptop, phone, tablet, etc.).

Some OATH hardware keys show the code on a built-in display. Others don’t have a display, so they rely on authenticator software installed on your phone or computer to retrieve the codes from the hardware key and show them. Some authenticator apps can automatically type the code into a login page. Note: Don’t confuse a hardware key’s associated software authenticator with the software-only authenticator described in 4.5.

There are two OTP protocols: TOTP (time-based one-time password) and HOTP (hash-based message authentication code [HMAC]-based one-time password, commonly called event-based OTP). TOTP is more popular, although many hardware tokens support both.

There’s a one-time enrollment process, where you connect to a service’s website or app and choose the option to use an OATH TOTP or HOTP security key for authentication (or choose the generic “authenticator” option). You need to get the shared secret key or seed from the service, usually by scanning a QR code or by typing (or copying/pasting) the secret key that the service shows you. (Some hardware keys are preprogrammed with one or more seeds, so they must be specially configured.) You edit or type a name to identify the service (e.g., Google, Facebook, My Bank, etc.) so you can find the right OTP code later, if you use multiple services.

Once the device has the secret key, it feeds it into a cryptographic algorithm to generate a one-time code based on the current time (for TOTP) or the time that has elapsed since the enrollment process started (HOTP). You enter the code on the setup screen so the service can make sure it matches the code it generated from its own copy of the secret key.

From then on, each time you want to log in, you insert the hardware key (if it’s USB), or hold it near your computer or phone (if it’s NFC or Bluetooth) and perhaps tap a spot, or press a button to see the current list of codes, each identified by the name you gave it. Some hardware keys have a fingerprint reader or a keypad to enter a PIN for added security, or the associated authenticator software may give you the option to add a password.

4.6.2 FIDO U2F hardware security key

A U2F security key (or FIDO key or OTP token) plugs into a USB port on your computer or phone, or uses wireless NFC (near-field communication) or BLE (Bluetooth low energy) to respond to a login request by sending an encrypted message through your computer, phone, or tablet to the service you’re logging into.

There’s a one-time enrollment process, where you connect to the service’s website or app and choose the option to use a security key for authentication. For a USB key, you’re prompted to plug it in and usually tap a spot or press a button on the device. For a wireless key (NFC or BLE), you may be prompted to tap it against your phone or computer and tap a spot or press a button on the key. Some hardware keys have a fingerprint reader or a keypad to enter a PIN for added security. You are usually prompted to enter a name for the service so you can select it later when logging in. A public/private key pair is generated, the private key is securely stored in the hardware key, and the public key is sent to the website or app. (See Public/private keys for more.)

4.6.3 Advantages and disadvantages

General advantages of hardware security keys:

- Physical factor - You have to possess the device to log in, reducing the risk of unauthorized use.

- No Internet connection is needed – After the initial setup, the codes can be generated and used offline.

- Simple to use, although enrollment can be confusing.

- Many support all three protocols: OATH, FIDO U2F, and FIDO2 (passkeys).

Advantages of OATH (generating an OTP):

- More secure than software authenticators, since the secret key (seed) is stored in tamper-resistant hardware that’s difficult to hack.

- One-time passwords can only be used once, and time-based passwords change frequently, reducing the window of attack.

Advantages of FIDO U2F and FIDO2 (using USB, NFC, or Bluetooth):

- More secure than software authenticators, because they use private keys that are stored in tamper-resistant hardware that’s hard to hack, and the service only has the public key.

- Immune to phishing – You don’t see the login code sent by the device, so you can’t be tricked

into giving it out.

- Tech note: There is a man-in-the-middle (MITM, aka Adversary in the Middle, or AitM) attack, where you are phished to a fraudulent site that proxies the legitimate site’s login page and behind the scenes tells the legitimate site to use cross-device authentication (CDA) to get a QR code that the fake site displays. When your device scans the QR code and returns a signed assertion, the fraudulent site can intercept it to access your account. This only works if the legitimate site doesn’t enforce proximity with Bluetooth or NFC. (See Expel’s blog for more.)

General disadvantages of hardware security keys:

- Limited number of “slots” – Some older or simpler hardware keys can only support one account. Others support 10, 30, or more than 100. Most hardware security keys don’t have management software that can delete keys to make room for new ones.

- Can only be used as a second login factor, not for passwordless login.

- Can be lost or stolen – potentially allowing unauthorized access (if your password is also compromised) until the old device is revoked at every service.

- Can break – Most are rugged, but they can be run over, dropped (especially bad if plugged into a laptop or phone that lands key side down), overheated, or just quit working.

- Inconvenient – You have to carry a hardware device. USB-only versions must be plugged in. If the device doesn’t work or is not available, you may not be able to log in. If the device is lost or stolen, you must revoke it at every service and reregister with a new device.

- USB-only keys don’t work with many phones.

- Don’t work everywhere – May not be supported by your computer or by the service doing the authentication. In some cases, you might need different hardware keys for different services.

- Typically cost USD $20 to $95.

- Deploying and managing devices for a large group of users can be complex and time-consuming.

Disadvantages of OATH (generating an OTP):

- Hardware keys without a display require you to download and install software. The software interface can be confusing.

- Vulnerable to phishing – An attacker can try to fool you into revealing the code (see 5.3).

- Shared secret – The key is stored in the authenticator and at the service. If the key is stolen from the device (unlikely) or the service (more likely), legitimate codes can be generated.

4.7 Biometrics

Biometrics (“life measurements”) are a way to recognize a person based on their unique physical characteristics such as fingerprint, voice, iris, or behavior (e.g., unique patterns in the way they type, speak, walk, move a mouse, and so on.) For authentication, biometrics are the “something you are” or “something you do” factor.

In general, especially with modern mobile phones, biometric authentication using fingerprint or face recognition is more secure than a password. However, biometrics are rarely used without a second factor such as device possession or a password or secret key.

In almost all cases, part of what makes biometrics secure is that your biometric data is not shared or sent anywhere, or even stored in the device. The fingerprint image or face scan is transformed into a simple but still unique value, typically by hashing, which can be easily checked by the local device. The device then authorizes unlocking or sending an authentication key to the service you’re logging into. (See 4.8 for how this works with passkeys.)

Consider the keys to strength from section 2. A biometric hash is long (usually 32 bytes) and therefore hard to guess. It’s unique (it only matches you). It can’t be reused or stolen from a service (because it’s stored only on your device). On top of that, it’s resistant to phishing (you can’t tell it to someone or enter it into a fake website).

4.8 Passkeys

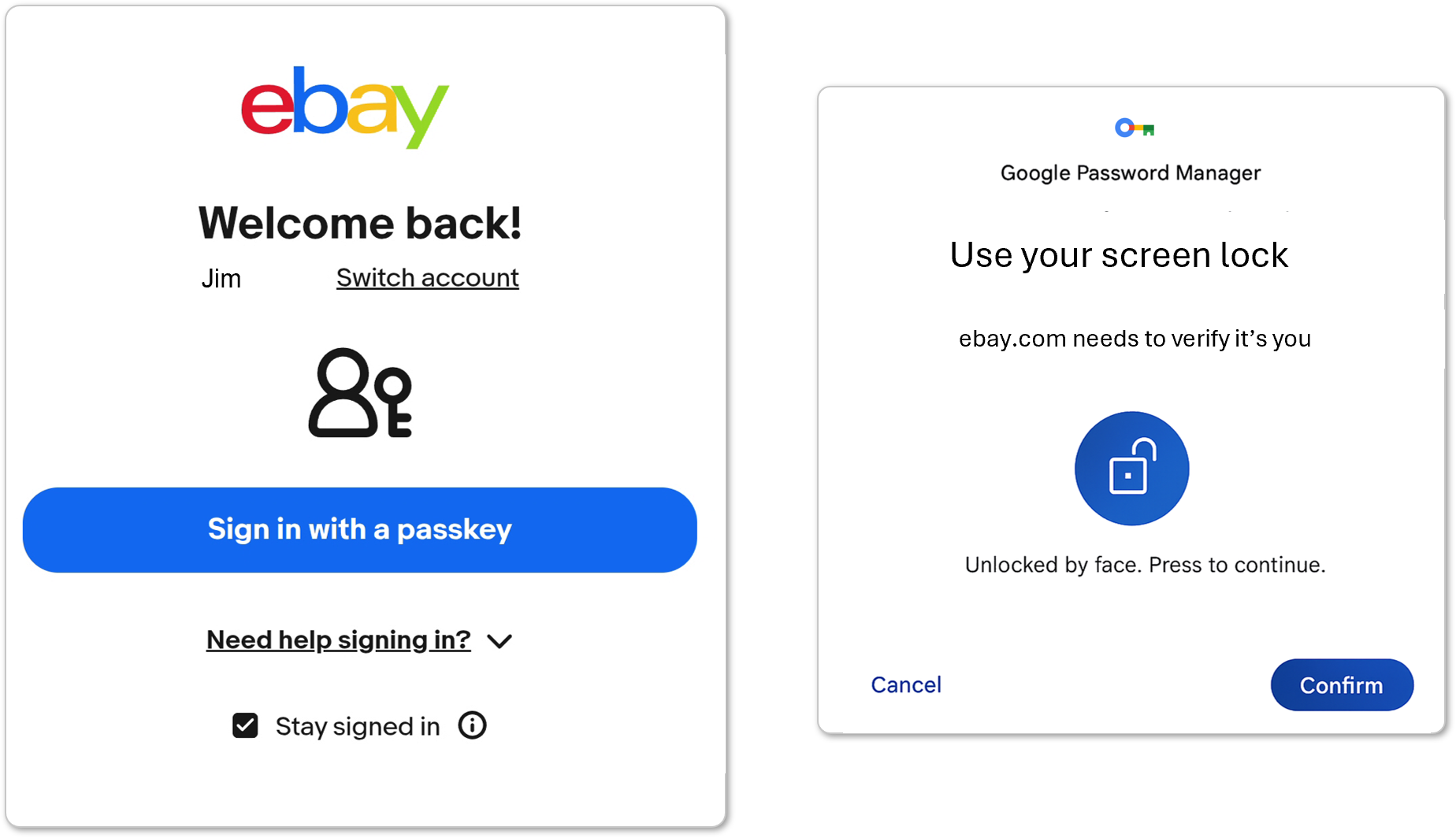

In a future utopia, we’ll use passkeys everywhere instead of passwords and other login mechanisms. Passkeys are more secure than passwords and most other login methods, and can be simpler and faster. Unfortunately, many passkey implementations are complex and confusing (see Passkeys Remystified - coming soon). Many websites and apps don’t yet support passkeys. Poorly implemented systems use a passkey but still require a username or password. Password-free utopia is still many years away.

A passkey is essentially a secret code, securely stored on your phone, computer, or other device, that logs you into a website or app. When you’re presented with the option to use a passkey to log in, you (usually) don’t need to enter a username or password — you just take the usual step to unlock your device with your fingerprint, face, PIN, or pattern.

The important difference is that neither you nor the service you’re logging into knows your passkey: you don’t think them up, you don’t have to remember them, and you don’t type them. Instead, you use software or hardware that manages the passkeys for you.

Passkeys were developed around 2018, and began to be adopted in 2022, in an attempt to deal with all the problems discussed above: weak and predictable passwords, password reuse, breaches of stored passwords, human error, phishing attacks, overload from dealing with too many passwords, and so on.

A passkey involves two factors — a device and an unlock step, so it replaces a password and a second authentication factor such as a text message or email. (See Are passkeys MFA?)

Passkeys use a modern approach of public/private encryption in place of the less-secure shared secret approach used by passwords and OTP authenticators (see 4.5 and 4.6). In simple terms, when you first set up a passkey to log in to a website or app, your device generates a private key that it keeps and a public key that it gives to the website. (See Public/private keys for details.) After that, when you want to log in, the website doesn’t ask for your username and password, instead it sends a message to your device asking it to authenticate you. Your device checks that it actually is you (scans your fingerprint or your smiling face, requires you to enter your unlock pattern, etc.), then signs the message (by encrypting it with your private key) and sends it back to the website, which verifies the signed message (by checking that your public key correctly decrypts the message), which proves it’s you logging in with the right passkey.

Since the private key is never sent to the website, it can’t be stolen. You don’t know the private key, so you can’t mistakenly give it to someone pretending to be legitimate, or enter it into a fraudulent website (i.e., you are invulnerable to phishing and man-in-the middle attacks). And it’s essentially impossible to guess. (The standard key size of 256 bits provides almost as many possible combinations as there are atoms in the universe.)

Passkeys (specifically the private key and additional information such as the account and website that it’s associated with) must be managed by an authenticator, which is hardware or software that creates the keys and later performs user verification before signing a login request with the private key. The authenticator can live in different places, which determines where your passkeys can be stored:

- On your computer or phone, managed by the operating system (OS), e.g. Apple iCloud Keychain, Windows Hello, or Google Password Manager on Android

- In the Apple Safari, Google Chrome, or Microsoft Edge browser, managed by the built-in password manager

- In a standalone password manager application

- In a FIDO2 hardware security key (see 4.6)

- In another FIDO2-compatible device, usually wearable, such as a smartwatch or ring

When you first create a passkey, you may see several options for where to save it. You might have to select “Other ways to sign in,” “Try another way,” or a similar option to see them all. Your choice of where to keep your passkeys depends on what devices you have and how you use them.

Where should I save my passkeys?

- Do you use a standalone password manager on all your devices?

It’s best to store your passkeys in the password manager, since most of them can sync passkeys across devices and different browsers. - Do you use the Google Chrome browser on multiple devices?

Google Password Manager syncs passkeys across Windows, Android, Apple, and Linux devices. Or consider a password manager, which will work with other browsers such as Brave, Firefox, and Microsoft Edge. - Do you use all Apple devices, such as a Mac and an iPhone?

It’s best to keep your passkeys in iCloud Keychain, which will sync them to all your devices, managed in the Passwords app. Or consider a password manager, which may have additional features. - Do you use the Edge browser on multiple devices?

As of fall 2025, Microsoft Edge syncs passkeys, using your Windows Account, to other devices where you use Edge. Be sure to choose "Microsoft Password Manager" instead of "Windows Hello or external security key" when you’re asked where to save the passkey. - Do you primarily use Windows?

If you choose "This Windows device" when Windows asks you where to save the passkey, it will be locked to that computer and won’t sync to other devices. If you have the Google Chrome browser installed, you can choose to save it to the Google Password Manager, which will sync it to your other computers with Chrome, as well as Android and ChromeOS devices. If you have Windows 11 and choose "iPhone, iPad, or Android device," the passkey can be saved to your mobile device. In this case, each time you use the passkey to log into a website on your computer, you’ll need to respond to a prompt on your mobile device, and perhaps scan a QR code. - Are there some websites or apps that you use only on your phone?

You might want to keep passkeys for those websites/apps on your phone, instead of a browser. They will usually transfer to a new phone. - Do you prefer using a FIDO2 hardware security key, such as a

Yubikey?

There’s usually an option to save passkeys to the physical key. This is a very secure option. Be aware that some hardware security keys can only store a limited number of passkeys. - Do you use Microsoft Authenticator or Entra ID?

Microsoft Authenticator creates device-bound passkeys. As of 2025, Entra ID only supports device-bound passkeys, including those stored on FIDO2 security keys, or cross-device (via QR code), but Microsoft is adding support for synced passkeys. Your admin may restrict Entra ID passkeys to device-bound only. - There are other variations and factors. For example, you can use Apple iCloud Keychain on Windows to access your passkeys, but it won’t sync them to your Windows PC; you can tell Google Chrome browser to store passkeys in Apple iCloud, and they’ll sync with other Apple devices, but they won’t sync with non-Apple devices. You may need to experiment a bit to determine the best place(s) to store your passkeys.

Caution: Don’t lock yourself out of your accounts by depending on only one passkey to log into the account where all your other passkeys are stored. In other words, don’t lock the key to your safe inside your safe without another way to unlock the safe. Be sure to have a backup or recovery method such as multiple devices, registering your phone and email with the account where you store your passkeys, perhaps registering a trusted contact’s phone or email, getting a recovery phrase, storing additional passkeys on hardware security keys, and so on. An emergency kit helps with this.

If your passkeys are stored on your phone but you’re logging into a website or app on your computer, a friend’s computer, or a public computer, you can usually link to your phone wirelessly by scanning a QR code, then select the passcode from your phone. The website may give you the option to create a local passkey on your computer to use the next time. (If you have a phone and two computers, for example, you could end up with three different passkeys for the same account, which is fine.) If you’re on a public computer, you should uncheck any "stay linked to this device" boxes and decline any offer to save a local passkey.

The same passkey can’t be used at more than one service. This is by design, so that a passkey can’t be used to track you across multiple websites and services.

Learn more about using passkeys with:

- Microsoft Windows

- Apple Mac, iPhone, iPad

- Google Chrome browser or Android phone

- Password managers: 1Password, Bitwarden, Dashlane, Enpass, KeepassXC, Keeper, LastPass, NordPass, Proton Pass, Roboform

- Hardware security keys: Yubico, Google Titan, Thales

Advantages of passkeys:

- More secure:

- Every passkey is unique, random, and strong. Unlike passwords, there are no weak or reused passkeys, or patterns that can be exploited. (Entropy ≈ 128 bits.)

- You can’t be tricked into revealing your passkey (phishing or clickjacking).

- Passkeys are automatically 2FA.

- Passkeys can’t be leaked. If a service is breached, the attacker only gets your public key, which doesn’t do them any good.

- Passkeys can’t be stolen by malware on your device or by someone eavesdropping on your Internet connection.

- Simpler, faster login – Potentially. Although there’s an extra initial setup step, and you may need your phone or other device to log in on your computer, the login process can be quick and simple, since you don’t need to enter a username or password (and type it again when you get it wrong), and you don’t need to wait to get a code that you have to type or paste. Case studies show that passkeys make logins two to eight times faster. Unfortunately, passkeys often don’t work as smoothly as they should.

- Unforgettable – Since you don’t memorize passkeys, you never need to reset your password.

- Portable and interoperable – Support for passkeys is built into every major browser and operating system, and can potentially sync across all your devices, but as of 2026 there are still many problems.

- Potentially shareable – Some password managers allow you to easily share passkeys with someone who uses the same password manager (including Apple Passwords and Google Password Manager), which is much more secure than sharing passwords.

- For implementers, less work and lower cost than using factors such as text message or email authentication (but only if they exclusively support passkeys for login).

Disadvantages of passkeys:

- Can be inconvenient – Although passkeys are ostensibly simple, you usually must confirm with a biometric scan or a PIN or pattern, sometimes on a separate device. On the other hand, a password manager autofills your username and password so all you need to do is click or tap the login button if you’ve already authenticated to the password manager.

- Inconsistent user experience – Each browser, website, app, and OS presents passkeys in a different way, sometimes with different terminology, which can be confusing.

- Device dependent – Passkeys may be tied to a specific device, such as a hardware security key or phone, requiring you to have it with you and unlock it.

- Often don’t work on non-owned devices – It may be difficult or impossible to log in on a public computer or friend’s device using your passkey if the passkey is not available on a portable device such as a phone or hardware security key, or if the other device isn’t able to connect to your phone (using QR code + Bluetooth + WiFI) or hardware security key (using USB, Bluetooth, or NFC).

- May not be shareable – Some password managers allow you to share passkeys with others, but they usually need to use the same password manager and perhaps be a trusted contact.

- May not be an option – Passkeys must be supported by the service you want to log into, and by the operating systems, browsers, or apps you use, so they may not work everywhere you want them to.

- Ecosystem lock-in – It may be difficult to switch platforms (brand of devices, browser, or operating system) or to move between them without recreating all your passkeys. This can be overcome by using a cross-platform password manager, and should be less of a problem as passkey exchange becomes more widely supported.

- Potential security weakness – Attackers may be able to work around passkeys to access your account. Or they could get to your passkeys by breaking into your password manager account (including your Apple, Google, or Microsoft account). Nevertheless, passkeys are significantly more secure than passwords, “magic link” emails, OTP codes, and other phishable authentication methods. See How secure are passkeys, really? for more.

- Could be restricted – Passkeys can’t be used from mobile devices in a sensitive environment where such devices are prohibited.

4.8.1 Security credentials (vs. passkeys)

Have you created passkey at a website, only to find that it doesn’t appear in your password manager? This usually means the website developers are confused about credentials.

The FIDO2 specifications define two types of credentials (or keys): discoverable and non-discoverable. (Formerly called resident and non-resident.)

Passkeys are discoverable credentials, which means a website or app can ask your device to authenticate you without needing a username or other identifying information. Your device checks its stored passkeys for one or more that are tied to that website or app, and after you verify with the unlock step, the passkey identifies you to the website or app.

Non-discoverable credentials are not stored in your device, so the website or app must get information from you, usually a username, to look up your ID and public key in its database in order to authenticate you, using your device.

Both types of credentials enable passwordless authentication, but only passkeys (discoverable credentials) enable usernameless authentication, which simplifies the login process. Passkeys can be device-bound or synced, but non-discoverable credentials are always bound to a single device. (Passkeys are explained in more detail above.)

Both types of FIDO2 credentials can be stored on an external hardware security key or managed by software such as a password manager. Passkeys (discoverable credentials) usually replace username, password, and 2FA. Non-discoverable credentials typically replace only the password, or are used for 2FA along with the username and password. The older FIDO CTAP1 (U2F) specifications first defined non-discoverable credentials, but U2F credentials can only be stored on a compatible hardware security key, and are typically used only for 2FA.

Unfortunately, many recent introductions of “passkeys” are actually misnamed implementations of non-discoverable security credentials. You may be prompted to “create a passkey,” but when you look in your password manager, there’s no passkey for that website. It still works — you can log in using the specific device where you created the software security key, but you have to enter a username (and maybe a password), and there’s no passkey to sync or manage. There’s nothing you can do about this, other than complain to the service that their developers are clueless, and that they need to implement real passkeys. (This is often as simple as fixing the code to set authenticatorSelection.residentKey to "preferred" or "required" instead of leaving both residentKey and requireResidentKey undefined, which seems to be the common mistake.)

4.9 Federated identity and social login

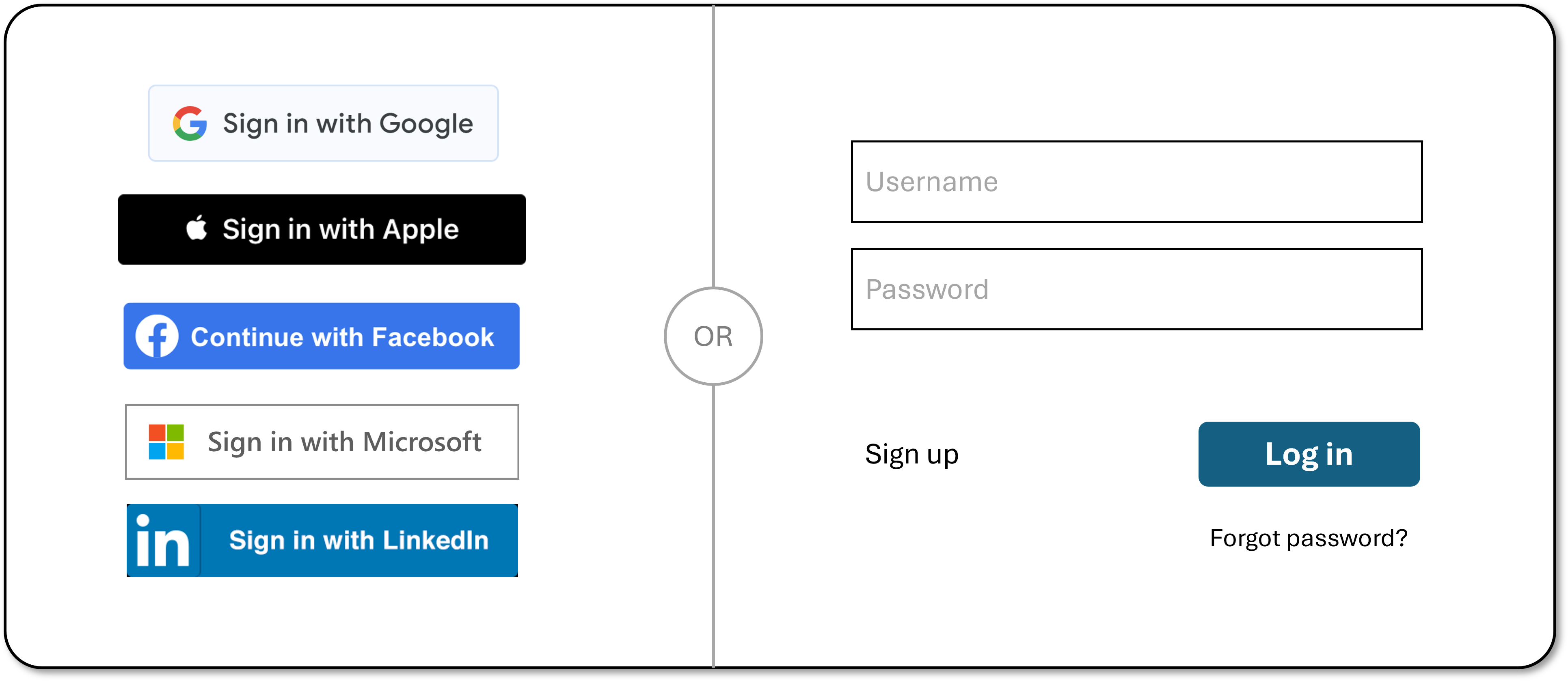

Federated identity is where a single service shares your identity (your login credentials and other information about you) to multiple organizations, services, and applications. For example, if you use your Amazon account to login to websites or apps for Amazon, Goodreads, and Wordpress, Amazon is serving as your identity provider to all these services.

Federation can function within a single organization, in which case it’s often called single sign-on (SSO). For example, a corporation’s employees may be able to log in to different company applications (email, customer management, payroll, etc.) using a single username and password. You can log into Microsoft Windows, Word, Excel, Outlook, OneDrive, SharePoint, Skype, etc. using a single username and password or a single passkey.

Social login (or social sign-on, social authentication, or third-party authentication) is where one organization serves as an identity provider for other organizations. When you are about to sign up with a new service and are given options such as “sign in with Google,” “connect with Facebook,” “continue with Apple,” or “sign up with Microsoft” as alternatives to “sign in with email,” these are social login identity providers. Instead of signing up for a new account with your own email and/or username, and coming up with a new, unique password (you always do this, right?), you allow the social network to provide your identity and other info to the service you’re signing up for. Social login is a form of identity federation.

(Top social login providers, using their preferred logo, text, and button format.)

The biggest concern with using social login is that you cede more control of your digital identity and personal data to a single corporation. One whose goal is to make money off you. Instead of having isolated accounts at different services, you allow one business to aggregate and manage your identity. Social login makes it possible for multiple services to track you — and advertise to you. Social networks usually share information about you, including your name, birthday, picture, location, friends, and activities. Some social networks allow you to choose exactly what you share, others don’t. Apple gives you the option to have a random email address generated to hide your regular email address. Most give you a page to see what you’ve shared with whom. Here are the links to the sharing pages for Apple, Facebook, GitHub, Google, LinkedIn, Microsoft, and X/Twitter.

According analyses by login providers Okta and Descope, about one third of logins are social, with the most common being Google (by far), Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Salesforce, GitHub, and LinkedIn. (Note that Microsoft owns GitHub and LinkedIn, but they operate as mostly independently identity providers, although, for example, LinkedIn may share data to enable personalized ads on Bing and other Microsoft services.)

A few federated identity providers are not social networks, such as Microsoft Azure AD and ID.me (used by government as well as healthcare organizations and consumer brands), but the functionality is similar.

Social login service providers such as auth0, Firebase, Okta/Auth0, OneAll, and OneLogin have APIs that make it easy for developers to offer social login for as many as 30 or 40 identity providers, although they recommend only presenting three or four to avoid a cluttered interface.

Advantages of social login:

- Easier – No need to create a new account.

- Faster – If you’re already logged in to the social network, you may just need to click a “continue with” button.

- Less password overload. You don’t need to keep track of so many passwords.

- Trust – You may trust the social network to keep your password and other information safe more than you trust the service you’re connecting to.

- Social network integration – Some services feed fun or interesting data back into your social network account, help you connect to new friends, and so on.

Disadvantages of social login:

- Less control – Your identity and personal data are managed by the social network, which may share it and allow you to be tracked. (See details above.)